Return of the crisis group

In the face of a global pandemic, the G7 this year will hark back to its erstwhile status as a crisis group – but it must still address the pressing issues that weave an unbroken thread through the annual summits, writes Karoline Postel-Vinay research professor, Sciences Po, Paris

The world in which the 2019 G7 summit took place seems far away. Major crises were unfolding in the international community in the background of the Biarritz meeting: a US-China trade war, the burning Amazon rainforest, escalating military tension in the Strait of Hormuz, to name a few. Most were linked to long-standing, complex issues such as climate change, and most remained present throughout 2020.

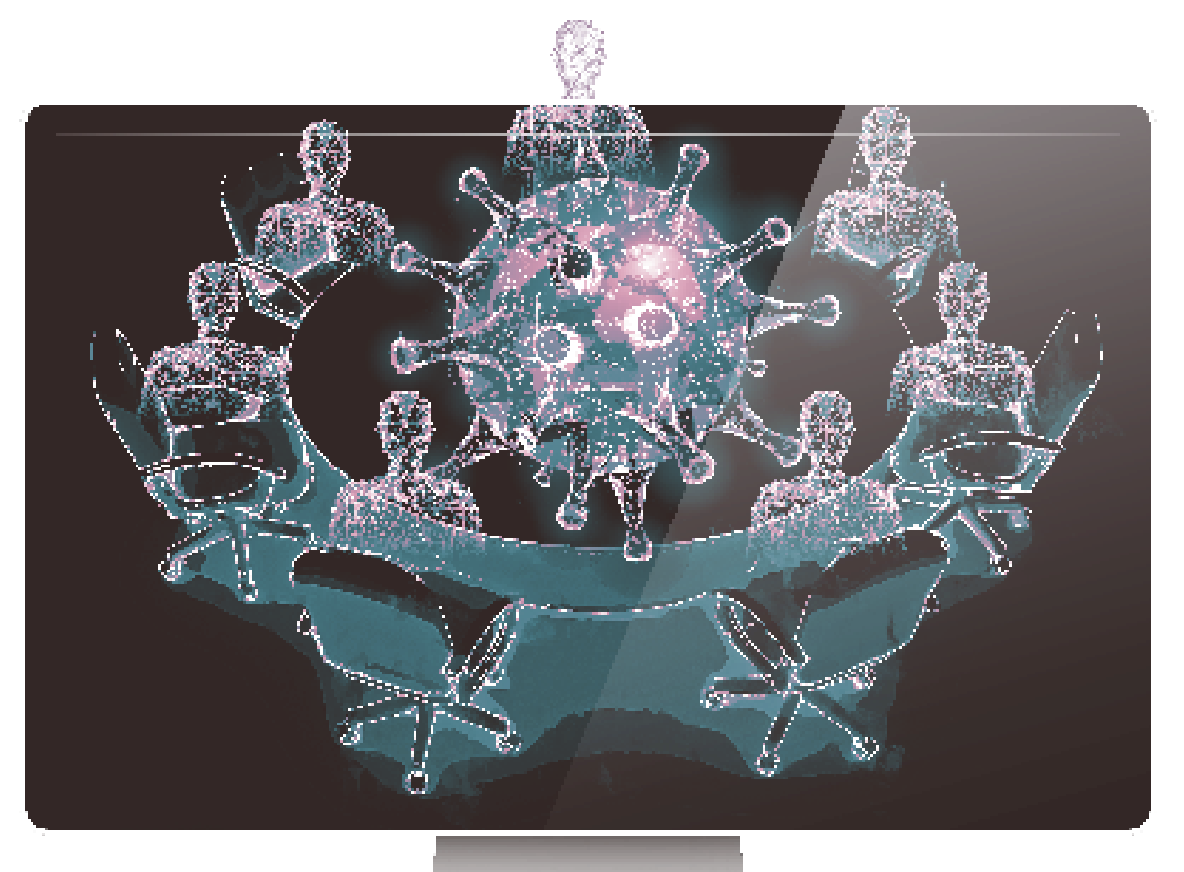

Yet the pandemic that has unfolded globally since January 2020 constitutes a ‘meta crisis’ that either overshadows pending issues, such as nuclear weapons dissemination or terrorism, or amplifies others led by economic and social inequalities and sustainable development.

The 2020 G7 is thus returning to its ‘crisis group’ status that defined it when the United States, in 1973, helped launch the informal meeting of the ‘group of four’ in response to the oil crisis. The G8 (with Russia from 1998 until 2014) regained that status amid the financial crash in 2008, which led to the establishment of the G20 summit as the premier forum for international economic cooperation. The significance of the current health crisis and its many ramifications will need to be assessed in the long run. Yet the extraordinary circumstances in which the G7’s 2020 meetings took place, starting with its emergency videoconference on 16 March, indicates the momentous challenges now confronting the G7 leaders.

Restored common interest

The pandemic and its immediate impact have dominated the leaders’ agenda. But as the G7 must ensure some continuity in its yearly summits – not least because other pressing issues unrelated to COVID-19 still require global coordination – the group will have to address the questions discussed at the Biarritz Summit in 2019. Its achievements and shortcomings must be taken into account in order to lay the foundations for a constructive meeting. Some commentators consider Biarritz’s major success to be restoring momentum after the confusion that marked the end of the 2018 Charlevoix Summit.

A clear commitment to cooperate among the seven major democratic powers is crucial for any significant input to global governance, and the 2019 French presidency was so determined to avoid a disappointing conclusion that it lowered expectations – giving up the idea of a collectively agreed statement – while securing enough grounds for unanimous agreement. A minimal final declaration was eventually produced, but more importantly a sense of common interest and trust was re-established among the leaders. This is essential when the G7 has once again become a crisis group. The leaders’ monthly videoconferences in March and April to respond to the pandemic were a positive indication that, despite strategic differences, the goodwill demonstrated at Biarritz should prevail in some measure.

Health as a global good

Other progress made at Biarritz is also noteworthy. The converging views on global health, and specifically the decision to increase financial support for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis, was an important reminder that health is not only a concern for national governments but a global common good as well. The relevance of that decision is acutely obvious today.

Other decisions must be underlined, such as a G7 and Africa Partnership. The commitments on digital transformation and women’s social and economic empowerment are relevant and likely to become ever more pressing. The numbers of COVID-19 cases recorded by many African countries are still relatively low compared with data coming from Asia, Europe and North America, but rising fast. Global health and Africa experts, along with the World Health Organization, have warned of the catastrophic and multidimensional impact the pandemic could have here. This should be high on the agenda. Based on its shared values, the G7 could propose a strong and coherent contribution to Africa’s response to the impending crisis.

making a difference

Such a contribution, and the task of addressing the unfolding global economic crisis – a task that in all likelihood will be handled better by the G20 – falls precisely within the area where the G7, because of its size and its relative homogeneity, can make a difference.