G20 performance on climate change

G20 members are ramping up climate discussions, but inconsistent compliance with commitments underscores the need for stronger action and global cooperation

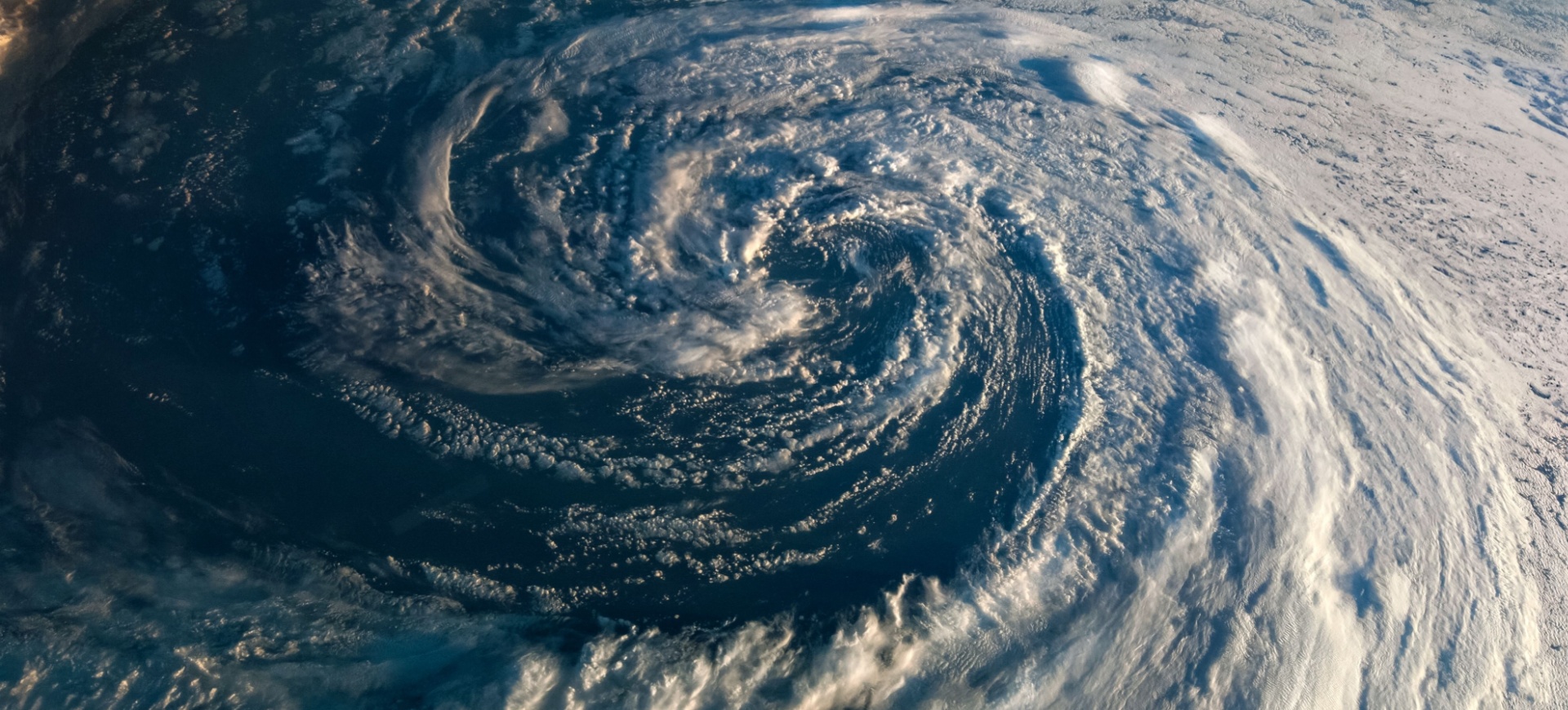

Whether you’re following breaking news from the World Meteorological Organization on sweltering heatwaves in Asia and Europe, tracking alarming statistics on drought and famine in Sub-Saharan Africa from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or watching reality TV stars discuss the challenges of selling real estate in California where torrential downpours trigger mudslides, the creeping normality of the climate crisis is inescapable. G20 countries, representing most geographic regions of the world, about 80% of global gross domestic product, 75% of global trade and 60% of the global population, play a decisive role in putting the brakes on the fossil fuel–powered train chugging humanity towards collective catastrophe.

Deliberations

Since their start in 2008, G20 summits have given 9% of their public deliberations, recorded in their communiqués, to climate change. Their first 11 summits, from 2008 to 2016, dedicated less than 5% at all but one summit, for an overall average of only 3%. The 2017 Hamburg Summit, led by Germany’s Angela Merkel, shone a bright spotlight on the Sustainable Development Goals and increased G20 climate deliberations to 10%. Deliberations fell

to 5% the next year, in Buenos Aires, but rebounded to 10% in Osaka in 2019 and stayed high.

The 2020 Riyadh Summit gave 12% to climate change. The 2021 Rome Summit gave an unprecedented 31%. The 2022 Bali Summit gave 22% and the 2023 New Delhi Summit gave 27%. Thus, since Hamburg’s 2017 ‘SDG summit’, the G20 has given 17% of its deliberations to climate change. From 2020 to 2023, it gave 23%, despite the Covid-19 pandemic and two regional wars threatening global security.

Decisions

Since 2008, the G20 has made 152 commitments on climate change, averaging 4% per summit. Up to 2016, it made fewer than 10 per summit, bar one. Thus, from 2008 to 2016, an average of 3% of all commitments per summit were on climate action, matching the percentage of public deliberations on climate change in this period.

That mirrored pattern continued: the number of climate commitments increased to 22 in 2017, plunged to three in 2018 and rebounded to 13 in 2019. But after another plunge to three in 2020 came a sustained relative high of 21 in 2021, 18 in 2022 and 19 in 2023.

However, between 2017 and 2023 G20 leaders averaged only 6% of their commitments per summit on climate change, rising to only 7% in 2020–2023. Thus, the rise in decisions was lower than that in deliberations.

Compliance

G20 members’ compliance with the 52 climate commitments assessed by the G20 Research Group since 2009 averaged 73%, just above the all-subject average of 71%. Average compliance for the first 11 summits, from 2008 to 2016, with the least deliberations and decisions, was 70%. From 2017 to six months after the 2023 New Delhi Summit, compliance rose to 78%. From 2020 – when deliberations and decisions stayed relatively high – to six months after the 2023 New Delhi Summit, it was 86%.

By member, the highest climate compliers were democratic European and G7 members: in the 90th percentile are Germany (94%) and the United Kingdom (92%), and in the 80th percentile are France (89%), the European Union (88%), Canada (88%) and Australia (84%). In the 70th percentile is Asia, with Korea (79%), China (73%) and Japan (72%), and also Italy (72%). In the 60th percentile are the Americas, with Mexico (65%), Argentina and the United States (64% each), and Brazil (57%), and also India (66%). In the 50th percentile are Indonesia (57%) and South Africa (53%). At the bottom are more autocracies: Russia (41%), Türkiye (39%) and Saudi Arabia (36%).

Causes and corrections

Some patterns appear in the data. First, G20 ministerial meetings matter; years with pre-summit environment and climate change ministers’ meetings had higher compliance than those without. From 2009 to 2018, when no ministerial was held, compliance averaged 70%. From 2019 to 2023, when there was a ministerial, compliance was 82%.

Second, working with and for the core multilateral organisation and international legal instrument helped, as commitments referencing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change averaged among the highest compliance, at 84%.

Third, short-term deadlines helped, as commitments with a six-month or shorter timetable averaged 85% compliance, while the one with a one-year timetable had 50% and the one with a multiyear timetable had only 43%.

Fourth, commitments that invoked the concept of sustainability or sustainable development averaged 73% compared to 68% for those that did not.

Fifth, climate finance has been a major challenge, as commitments to mobilise money for climate action averaged among the lowest compliance, at 64%.

Conclusion

To increase compliance, G20 leaders at the 2024 Rio and 2025 Johannesburg summits should:

- Further institutionalise the environment and climate change pre-summit ministerial meetings, and add joint meetings with finance and health ministers;

- Make more commitments that support the UNFCCC and its outcomes, including the Glasgow Pact;

- Make more commitments with very short-term timetables and clear, specific goals for reaching long-term, ambitious targets;

- Link sustainable development with climate commitments, led by SDG 13 on climate action; and

- Raise the trillions of dollars needed to stop the runaway climate train, while also ending subsidies and putting major brakes on all investments into all fossil fuels.