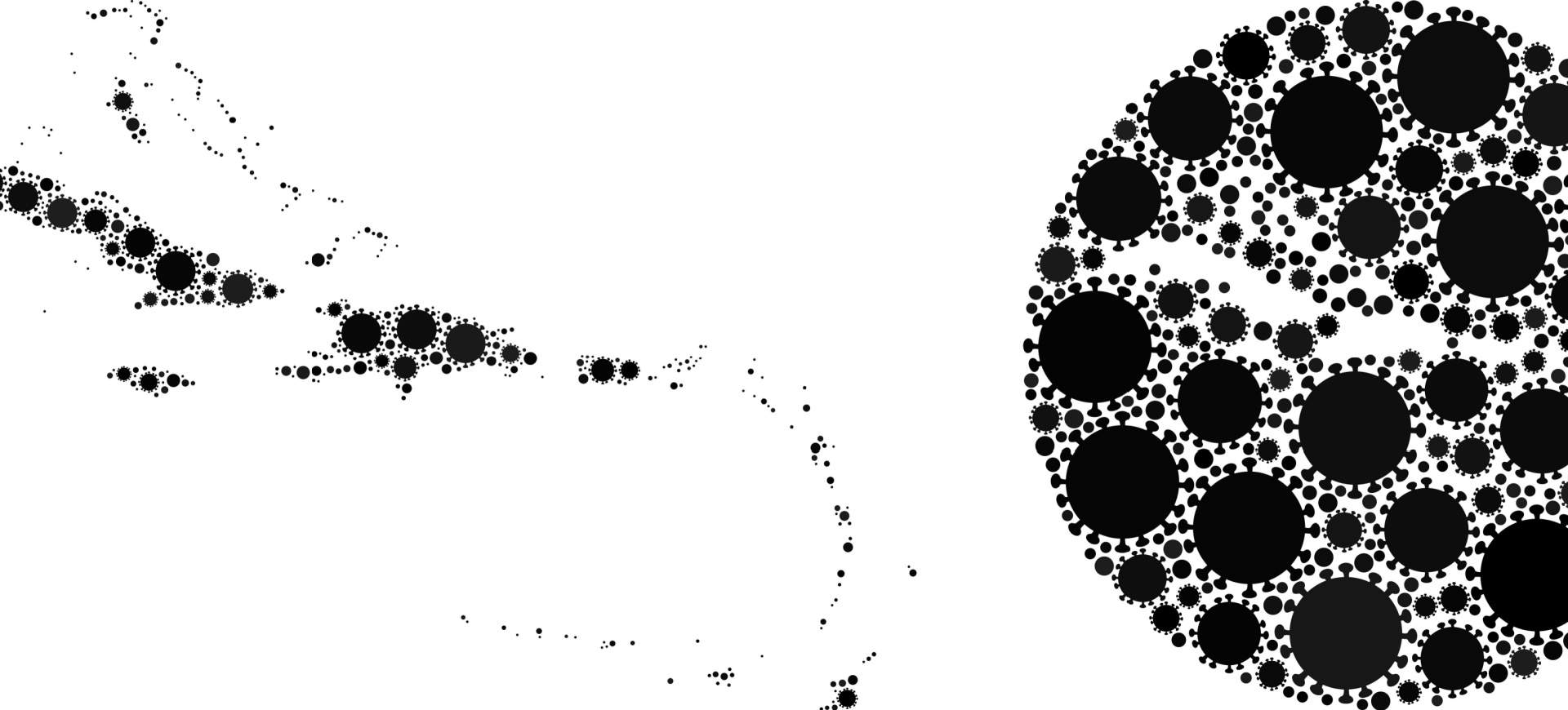

Better health in the Caribbean and small island states

Another pandemic is an evolutionary certainty. What is less certain, however, is how effective our response will be – and whether we can ensure it is equitable

How is the health of people in small island developing states, such as those in the Caribbean, harmed by the effects of Covid-19, slowing economic growth, inflation, indebtedness and climate change?

Covid-19 illustrated the importance of health in all policies, yet health financing is seen as draining the public purse. The medical model reigns in healthcare provision, where expensive curative care is better resourced than cost-effective prevention measures such as immunisation. These challenges reduce the available health spending for those of us in SIDS. The burden of out-of-pocket expenses for health care is growing. Health indices will not be good, especially for those with chronic diseases or the vulnerable, including children who did not get immunised, or the marginalised, including climate and Covid-19 migrants without access to health care.

There is a silver lining: humanitarian assistance for Covid-19 improved systems for critical care, expanded the range of immunisation equipment for ultra-cold chain vaccines, and improved systems that address vaccine production and match supply with demand more equitably.

The harmful effects of climate change are more real in SIDS. We have evidence in the Caribbean from unprecedented flooding in the past three years, ongoing sargassum problems affecting our coastlines and vector-borne diseases, and a critical tourism sector that depends highly on sustained livelihoods.

How are their governments and societies responding?

Infection prevention and control measures became life lessons that people absorbed, even if they grumbled.

Mental health stigma significantly diminished because everyone was forced into disturbing life-altering circumstances, and anyone could develop mental illness. People became entrepreneurial and more community minded.

Caribbean governments banded together and showed citizens that their health mattered by curtailing life-threatening situations.

However, the inevitable realities of those policies meant that governments began focusing on bringing economic activity back. Admirably, infection control measures lasted.

Caribbean governments also worked together to address the economic disasters that beset them.

Reopening the Caribbean’s tourism- dependent economies has required immense coordination between public health authorities and the private sector. Despite resource constraints and other external challenges, government leaders have made navigating through these new paradigms easier.

How is the Caribbean Public Health Agency countering these constraints?

CARPHA has partnerships to strengthen systems to mitigate the impacts of climate change on environmental and human health. Making systems more climate resilient can only be accomplished through collaboration.

We are working on a pilot project for climate resilience with the Pan American Health Organization, funded by the European Union; a training programme on building codes for harvesting rainwater, funded by the Caribbean Aqua-Terrestrial Systems and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; and an EU/CARIFORUM project on water and sanitation, early warning systems, climate-resilient water safety planning, food safety plans, and capacity building in leadership in climate change and health.

The Caribbean Health-Climatic Bulletin is a collaboration among CARPHA, PAHO and the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology to help health professionals prepare for favourable or inclement climate conditions.

The Tourism and Health Program protected workers and built confidence with the Caribbean Travellers’ Health Assurance Stamp for Healthier Safer Tourism; seven hospitality health, safety and environmental sanitation standards; technical guidelines for safe work and reopening; training in health and safety measures for Covid-19 and other infectious diseases; confidential electronic monitoring and response systems; support for tracking and reducing illness spread through rapid information sharing and response; advocacy and promotion campaigns to foster measures for Healthier Safer Tourism and vaccination; and the Covid-19 Tourism Task Force to support health measures for safe tourism.

What advances has it made?

CARPHA is celebrating 10 years. An increase in our core budget, financed by member states, was approved. Corporate functions are being improved through EU funding for risk management, a new strategic plan and enterprise resource planning. We upgraded systems to combat cybersecurity attacks and improved communications.

CARPHA implemented integrated surveillance, improved disaster preparedness and response, and updated our partnering policy.

Our annual research conference continued during the pandemic.

CARPHA built trust with its members.

What tasks and challenges remain?

Health financing has declined since the pandemic but the weaknesses revealed still remain. The global health workforce is tired, and the Caribbean region remains under-resourced – yet still other regions recruit from us!

How can G7 leaders at their Hiroshima Summit best help the Caribbean and SIDS?

G7 leaders must understand that despite significant Covid-19 fatigue, we still have the weak systems and frank breaches in health security that have enabled the pandemic to last so long. Those breaches are widening, and exhausted health staff are unlikely to manage effectively if similar situations develop.

G7 leaders must not waste this crisis. They must immediately fix those glaring weaknesses: support the Pandemic Fund; address the drivers of climate change, which also drove aspects of Covid-19; and make policies that block the causes of non-communicable diseases, which made so many people vulnerable.