An agenda to tackle the politics of real problems and real people

Implementation of the universal healthcare agenda requires the efforts of multiple agencies, sectors and leaders… and a new way of talking about health

By Mit Philips, health policy advisor, Analysis Department, MSF in Brussels, Belgium; Caroline Voûte, health policy advisor, Programmes Unit, MSF in London, United Kingdom; and Kerstin Åkerfeldt, health policy and advocacy advisor, Analysis department, MSF in Brussels, Belgium

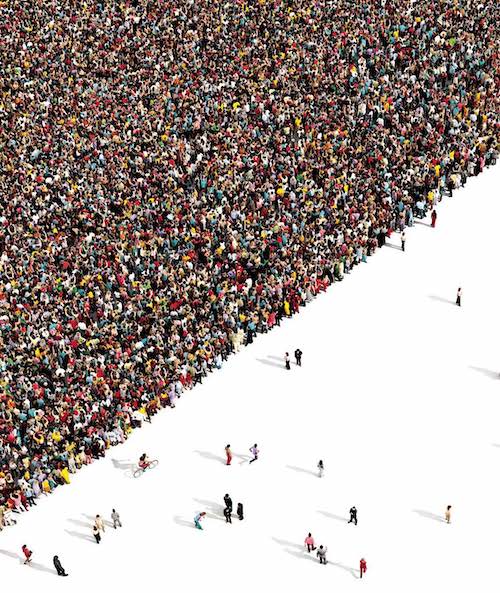

Across the world, every day, patients are denied access to health care. People are stigmatised, marginalised, neglected, denied their rights by society, state or the international community. Health care is often hardest to obtain for the poor, and for people affected by crisis or forced from their homes. If the stated ambition of universal health coverage ‘to leave no one behind’ is to be made reality, people – including the most vulnerable – must be at its heart.

The universal health coverage agenda cannot be delivered by the health sector alone. It must be a collective effort, and one that focuses on the needs of patients and communities. Without real political determination, inequity and precariousness will remain unchallenged – official policies will continue to make people ill.

Yet the current political discourse on global health is not encouraging. It echoes the precipitous economic models of the 1990s, once again making health investments dependent on countries’ potential economic capacity to pay or pay back. Countries with disproportionate health burdens struggle to make universal health ambitions fit within restricted budgetary and fiscal spaces.

International solidarity seems to be increasingly limited to those health issues fitting the global security agenda, migration deterrence policies or trade interests. ‘Innovative’ funding, loans, bonds, private and blended financing, all promise to compensate for dwindling health grants. However, for universal health coverage to deliver, saving lives and reducing the suffering caused by disease must always take precedence over considerations of return on investment.

Ambition cannot be limited to administrative coverage models that take years to translate into concrete access to health care. It should start to make a difference for patients in the real world, right now. We must focus on what those in need are struggling with today: patients forced to pay for essential care, insufficient frontline workers, scarce or interrupted stocks of key medicines.

When vulnerable people are forced to pay for care, a negative chain of events is triggered. User fees lead to reduced quality services, increased financial distress, and delays or exclusion from care. Médecins sans Frontières has repeatedly documented how user fees lead to substandard or incomplete treatment, delayed care seeking and exclusion from care.

How can we speak about universal health coverage when children with malaria are unable to afford a full course of treatment? When pregnant women asked to pay for HIV screening tests fail to protect their unborn child? When patients are detained in hospital until families find the money for medical bills?

These are far from anecdotal or innocent events. Recent MSF survey findings from Bili, a rural area in the Democratic Republic of Congo with a high malaria burden, show that in a quarter of cases of illness leading to death, no medical care was sought – with a lack of money cited as one of the major reasons.

The subsequent impact on communities can be devastating. The delay in seeking care leads to slower detection of epidemics and outbreaks. Data show that even small fees deter people who need care from seeking it, with the poorest or marginalised most affected.

For those deemed non-resident or without the correct papers, such as asylum seekers, migrants, refugees and displaced people, accessing health care is particularly difficult. National plans for universal health coverage tend to focus on their citizens, often excluding people on the move or without the right documents.

Just as Europe’s migration strategy harms the health of those it deters and detains, the lack of adapted mechanisms to realise universal health coverage for people living outside their home communities continues to reduce access to health care. Migrants moving through Greece struggle to receive vaccinations via the public system; in Jordan and Lebanon, refugees with non-communicable diseases are forced to interrupt treatment because it is unaffordable.

For universal health coverage to succeed, the vital role of frontline health workers must be recognised, with decent pay and recruitment according to health needs. Pay and recruitment are restricted in many countries now by wage bill ceilings and salary freezes. Continued access to affordable quality drugs must also be given greater attention and viewed as a crucial part of the universal health coverage jigsaw. The mobilisation of more domestic financing for health makes little sense if it is offset by the high price of medicines and vaccines.

In today’s narrative, the potential progress to achieving universal health coverage is often merely measured by a country’s intent of providing increased domestic resources for health, without much attention given to whether those commitments are sufficient or focus on the right interventions. Yet many governments lack the resources or the capacity to deliver medical services at the scale or pace that is being proposed.

Pressure on countries to mobilise more domestic resources for health may translate into pressure on patients; faced with shortfalls in national health budgets and waning international funding, countries such as Afghanistan, Mozambique and Malawi are already considering increasing patient payments for essential care.

Without realistic assessments of countries’ economic potential and careful consideration of restrictions and risks to health, cutting back international support might jeopardise previous achievements and delay progress towards universal health coverage. In several countries, simultaneous donor transitions away from aid have led to competing priorities and rationing.

The aid sector – including global health initiatives such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance – now seems to focus on increasing the leverage of domestic financing as a priority, including in low-income and crisis contexts. Discussions urgently need to (re-)engage the subject of international political will and its direct contribution to people’s health.

The agreed goal of universal health coverage by 2030 will remain a distant dream if those most in need are deprived from even the most basic of care because they cannot afford it. If it is to succeed, those people must be kept at the centre of political commitments, smart policies and equitable resource allocations.