A public health perspective on climate change and small island developing states: the Caribbean region

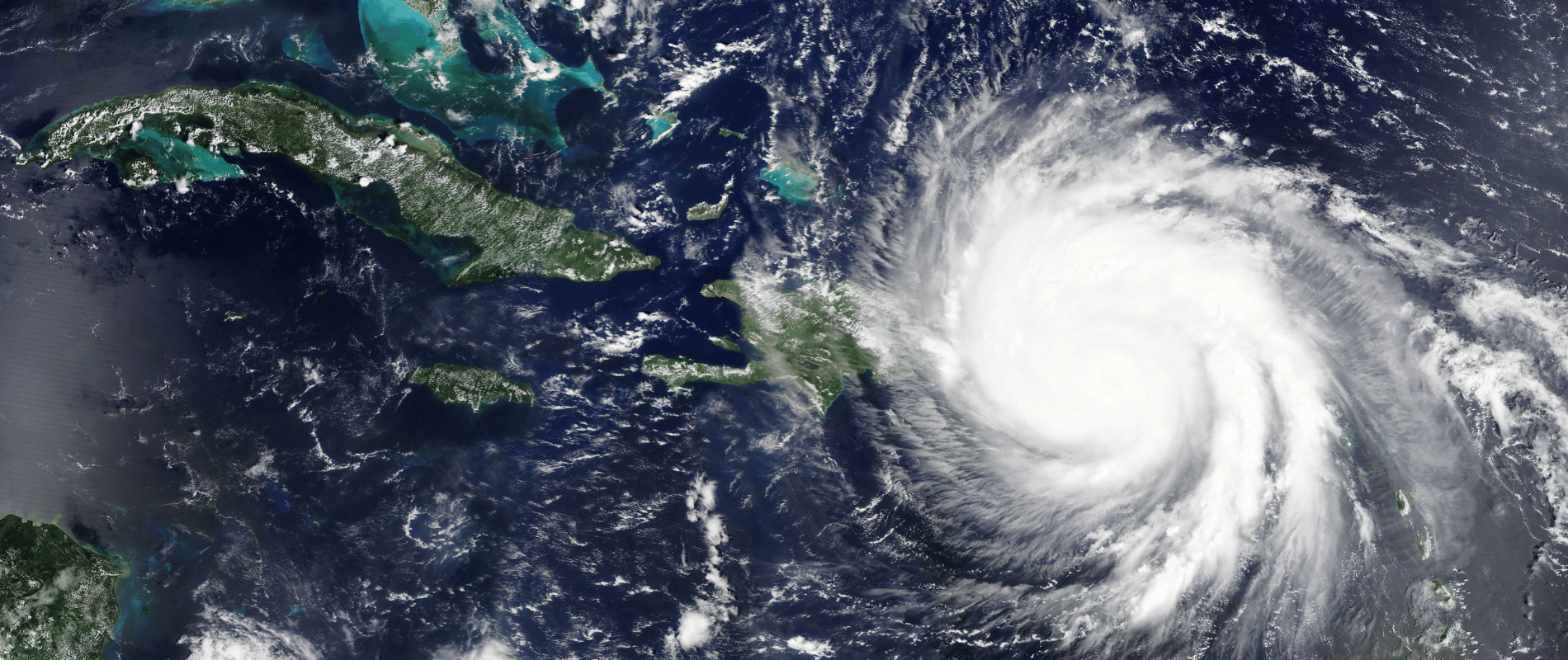

The Caribbean Public Health Agency, as the lead regional public health agency and an expression of Caribbean Cooperation in Health is mandated by its Inter-Governmental Agreement to support CARPHA member states in strengthening national health systems and coordinating regional responses to public health threats, inclusive of the impacts of climate change on health (1). The Caribbean small island developing states are prone to natural disasters, such as hurricanes, flooding and earthquakes. Of the 26 member states supported by CARPHA, 23 qualify as SIDS (1). The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction indicates that the Latin American and Caribbean region is the second most disaster-prone region, on a worldwide ranking (2). Climate change, driven by global warming, is the main driver behind the increasing severity of hydrometeorological events, as seen by the number of severe (Category 4 and 5) storms experienced by the region over the past five years, as well as longer, more intense drought periods (3). The impacts from such storms include the loss of lives and livelihoods, decreased human resources, heavy building infrastructural damage, reduced ability to provide public services and increasing disease incidence. Other impacts of climate change involve reduced food security through changes in arable land available for agriculture, rising sea levels, oceanic acidification and saltwater intrusion into water reservoirs (4).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change produced a special report, released in October 2019 (5), which acknowledges that the targets set in the Paris Agreement and nationally determined contributions are not sufficiently ambitious, and will not bring significant reductions in climate change impacts, particularly on the marine environment. The warming of global temperatures beyond a warming limit 1.5°C is estimated to destroy up to 99% of tropical coral reefs, and current projections by the World Meteorological Organization predict that this limit could be temporarily exceeded as early as 2026 (6).

There are two main pathways through which Caribbean populations and health systems remain highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The first is mediated through natural systems and overall ecosystem change, whereas the other is linked to human activities, such as migration (3). In the first pathway, shifting weather patterns and extreme climate events, such as, hurricanes, droughts, floods, heat waves and Saharan dust incursions result in adverse health outcomes. The latter include increased transmission of vector borne diseases, such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika (7); a higher incidence of respiratory disease, as well as water- and food-borne disease (from contamination of safe water supplies), and heat induced conditions such as heat stress and heatstroke, which can trigger cardiovascular conditions (3). Natural disasters such as hurricanes result in injuries, fatalities and mental health impacts that have long lasting implications for regional healthcare systems. As the Caribbean archipelago lies on the Atlantic Hurricane Belt, the region is faced annually by the threat of high intensity storms causing widespread damage. In 2024, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted an above normal hurricane season with 17–25 named storms (8). Hurricane Beryl, which severely affected the islands of the Grenadines, was the earliest Category 5 storm on record to hit the Atlantic basin (9). The devastation to these islands was great with a more than 98% loss of infrastructure recorded on Carriacou (10).

In the second pathway, climate driven human migration and population displacement can lead to loss of livelihood, heightened poverty levels, reduced work capacities and productivity. Taken together these effects limit progress towards attaining the Sustainable Development Goals by the Caribbean SIDS (11). Hence, in the Caribbean, climate adaptation and mitigation strategies across a range of sectors are essential to ensuring the future resilience of the region. To support this effort, SIDS have long started and continue the call for greater advocacy, supporting partnerships, evidence building, predictable and sustained access to low-cost, long-term financing and climate justice. This article aims to describe the regional efforts taken to date to strengthen the resilience of Caribbean health systems against the face of a changing climate.

METHODS

Collaborative partnership approach

The Caribbean region has adopted a multisectoral approach to strengthening health systems. Over the past decade, there have been numerous country and inter-agency collaborations among regional and international institutions such as CARPHA, the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology, the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre, the Red Cross, the Pan American Health Organization, the University of the West Indies and others. Such an approach seeks to strengthen interactions between multisectoral, multidisciplinary professionals for the creation and implementation of climate integrated early warning systems for health, health national adaptation plans and policies, food and water resilience planning, as well as infrastructural greening related to the primary healthcare sector. Among the Regional Caribbean Community (CARICOM) agencies, CIMH in collaboration with its network of national meteorological and hydrological services and the Consortium of Sectoral Early Warning Information Systems Across Climate Timescales (EWISACTs) coordination partners have been working together to develop tailored, sector-specific climate products. These tools provide evidence, which aid in strategic decision making. The consortium serves as a climate governance mechanism for the region, leveraging the expertise of technical organisations including the Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute, the Caribbean Water and Wastewater Association, the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency, the Caribbean Tourism Organization, the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association and CARPHA (12).

Adaptation and mitigation initiatives

Generating and implementing health national adaptation plans are key in assessing the vulnerabilities of Caribbean health systems to extreme weather events and linking to appropriate resilience adaptation and mitigation measures. HNAPs outline infrastructural investment and strategic actions that can protect health and build climate-resilient health systems. Inherent in this are the anticipation and transformation of public health to adapt to a changing climate, protect populations and manage health risks.

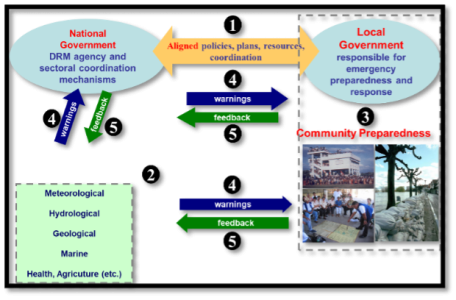

One key measure currently being explored in the Caribbean is strengthening surveillance systems through integrated surveillance. Integrated surveillance can greatly enhance the capacity of health systems to prepare and adapt to the increasing incidence of communicable and non-communicable climate-sensitive diseases. It involves the combination of multiple surveillance systems and data streams, for example, disease surveillance and weather surveillance data to improve the use of information for detecting, investigating and responding to public health threats. This integration of data improves the flow of surveillance information throughout the health system (13). Importantly, climate integrated surveillance can increase the preparedness and response capacities of health systems through the use of early warning systems. An EWS at the local level should be seen as an information system designed to enable decision-making of national authorities, and to enable vulnerable individuals and social groups to take actions to mitigate the impacts of an impending hazard. Ideally, the focus should be not only on improving hazard monitoring and prediction, but also on improving coordination between the national and local management agencies that assess risk and develop response strategies, and the public communication channels used to disseminate warning information (see Figure 1). Other adaptation efforts have involved the development of climate integrated food and water resiliency plans. This initiative between CARPHA, PAHO and Caribbean states looks at securing a safe and secure food and water supply, bearing in mind the expected climate changes over a 30-year period.

RESULTS

Climate integrated early warning systems for health

Health EWS work in the Caribbean over the past few years has centred on four CARPHA member states that were deemed ready to accept these interventions due to the results of baseline assessments and feasibility studies. On examining different surveillance datasets, vector-borne disease surveillance data appears to be consistently, well collected across these countries. These datasets are most fit for purpose, and incipient work has been underway since 2018 to collect all relevant data to generate preliminary models (7). Pilot implementation has been taking place in 2023/2024, followed by monitoring and evaluation to refine the systems set in place.

However, the EWS work is not conducted in isolation. Under donor-funded projects, CARPHA in collaboration with its partners, can holistically approach strengthening climate-resilient health systems in the Caribbean (14). The World Meteorological Organization has established the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology as the Caribbean regional climate centre. CIMH has worked with CARPHA on the EWS/impact-based forecasting process, and is also responsible for hosting the semi-annual Caribbean Climate Outlook FORUM (CARICOF), which provides key weather information to a range of sectoral stakeholders including health, agriculture, tourism, water and disaster risk management, to aid sectoral work programming. CARPHA, in conjunction with CIMH and PAHO, issues a quarterly Caribbean Health Climate Bulletin, which predicts the upcoming three-month climate outlook and potential impacts on health. Health practitioners can utilise this information to plan and prepare for appropriate interventions.

National climate resilient food and water safety plans

Between 2022 and 2024, CARPHA and PAHO have worked with Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago to develop national food and water safety plans. These efforts have been multisectoral and have involved stakeholders from health, agriculture, environment, meteorological services, works and infrastructure, national security, finance, gender and child affairs, as well as certain non-governmental organisations. Select high-priority catchment areas in each country were examined in terms of food production and consumption, water usage, supply chains, infrastructure and a range of other factors. Using a collaborative consultative process with the national stakeholders, as well as select data from both sectors, plans were formulated and revised as of 2024. The next step in this process is ministerial and financial review, as well as the establishment of national oversight committees to monitor progress post implementation. It is envisioned that CARPHA and PAHO will continue to provide technical support during this period. CARPHA has already secured funding to develop climate-resilient waste safety plans for two additional Caribbean states.

Health national adaptation plans and infrastructural greening

PAHO in conjunction with the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre has been leading the HNAP development process. The latter is seen as a critical strategy for assessing country readiness levels and proposing key strategic actions and financial planning that will be required to sustain measures for strengthening health systems. This approach also involves supportive involvement and commitment from non-health sectors working towards reducing the health outcomes of climate change on populations. To date, Belize, Saint Lucia, Bahamas, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines are either actively engaged or soon to commence work on this effort (15). In terms of infrastructural investment, PAHO has also been leading the smart hospital initiative through financing from the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (16). With seven Caribbean countries as beneficiaries, the aim of this effort is to build and retrofit health facilities on the islands to reduce their carbon footprint and withstand high intensity storm events, promoting healthcare service delivery post storm passage.

DISCUSSION

Progress on efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change and build regional resilience has been challenging. The region is acutely aware of the climate change threat and the need for relevant and timely implementation of adaptation and mitigation measures. However, difficulty in implementing change stems from several sources:

-The environmental and health impacts of climate change are still being explored. In some cases, there is not yet a clear causal relationship between weather changes and the attributed health impacts. This uncertainty creates difficulty in decision making. Political leaders may not have good evidence to aid advisors in giving clear guidance.

-The diversity in geography, geology and demography in the region means the countries have different needs and differing priorities. These competing priorities of communicable diseases, trade and tourism, education and others mean the financial resources available at the country level can be scarce.

-The diversity of needs and resources in the region makes it difficult to attain consensus. Some countries have the capacity to address the issues facing them, and work towards creating systems to protect them from future crises. Other countries lack the needed resources to keep abreast and will fall further behind.

-Increased funding will be required to implement these measures. The region has already secured support from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, the World Bank, the French Development Agency (AFD), the United Kingdom FCDO, the European Union, the Green Climate Fund, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Pandemic Fund, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and others. However, greater commitment is needed from the international community to prepare for the looming climate crisis.

-Sustainability of change at the community and national levels takes time to establish. Behavioural change is a constant endeavour. The ongoing effort and maintenance of change requires long-term commitments from local, national and international actors. Often commitments start strong but wane with time, and as new threats and priorities emerge.

-There is a lack of robust monitoring and evaluation systems. Monitoring and evaluation are a key follow-up intervention to measure the outcomes of implemented actions and their ability to strengthen health systems.

Real progress towards mitigation and building of resilience requires the region and agencies to come together to support individual and regional action. Through increased collaboration, countries can share the needed resources for making progress. To better understand the broader impacts of climate change, countries in the region need to improve their data capture and sharing capabilities. Some countries have implemented improved systems and automatic weather stations for monitoring weather patterns and environmental changes, such as sea levels and measuring Sahara dust. These stations are a good first step. However, additional monitoringstations are needed across the region to build on the scientific evidence.

Additionally, improved systems for surveillance of communicable and non-communicable diseases are needed throughout the region. Improved surveillance systems will enable CARPHA and its partners to monitor changes in the health of the communities. Monitoring these changes in the disease profiles of the region will help to better plan and direct the resources to address the health needs of the Caribbean people. CARPHA is engaged in rolling out District Health Information Systems (DHIS 2) in its member states, providing training for surveillance system data collection, analysis and reporting (17).

Along with improved surveillance systems, the region needs to agree and strengthen data-sharing policies. The surveillance data needs to be collated and shared with collaborating regional agencies such as CARPHA, CDEMA and CIMH. Sharing the data allows for a more complete picture of changes and trends. While the transfer of technical capacity to countries is an ongoing process, these regional agencies are better equipped than the individual countries to integrate and analyse the data on a large scale. This helps uncover and elucidate the broader impacts of climate change and allow countries to better work to mitigate related health impacts.

If well studied and understood, the lessons learnt in the Caribbean from the utilisation of appropriate adaptation and mitigation measures, will point to better strategies for other island and non-island communities and countries. Health considerations must be integrated into climate policy for promoting public health and equity. Increased funding will ensure the region will not lose the small gains that have been made and can amplify those into greater gains in the coming years. Furthermore, the adoption of a holistic approach that recognises the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health is crucial in safeguarding health for current and future generations.

Note: A shortened version of this article appears in Financing a Just Transition: Transforming Funding, Tackling Climate Change, edited by John Kirton and Ella Kokotsis (2024).

References

- Caribbean Public Health Agency. ‘Who we are.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://carpha.org/Who-We-Are/About.

- United National Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. ‘Overview of disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean 200-2022.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.undrr.org/publication/overview-disasters-latin-america-and-caribbean-2000-2022.

- World Health Organisation. ‘Climate change and health. Integrated surveillance and climate-informed health early warning systems.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/climate-change-and-health/country-support/integrated-surveillance-and-climate-informed-health-early-warning-systems.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Bases. 2021 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg1/IPCC_AR6_WGI_FullReport.pdf.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Special report: Global Warming of 1.5°C. 2019 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SPM_version_report_LR.pdf

- World Meteorological Organisation. ‘Update: 50:50 chance of global temperature temporarily reaching 1.5°C threshold in next five years.’ 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-update-5050-chance-of-global-temperature-temporarily-reaching-15°c-threshold.

- Lowe R, Ryan SJ, Mahon R, et al. ‘Building resilience to mosquito-borne diseases in the Caribbean.’ PLoS Biol. 2020; 18(11): e3000791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000791.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ‘NOAA predicts above-normal 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/noaa-predicts-above-normal-2024-atlantic-hurricane-season.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ‘Highly active hurricane season likely to continue in the Atlantic.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/highly-active-hurricane-season-likely-to-continue-in-atlantic.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. ‘Hurricane Beryl Situation Report #3,’ 4th July 2024. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.cdema.org/index.php/component/content/article/1740-situation-report-3-hurricane-beryl.

- United Nations. ‘Sustainable Development Goals – Climate Action.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-action.

- Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology. ‘Developing early warning information systems across climate timescales (EWISACTs) for climate-sensitive sectors in the Caribbean.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://rcc.cimh.edu.bb/ewisacts.

- World Health Organisation. ‘Integrated surveillance and climate-informed health early warning systems.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/climate-change-and-health/country-support/integrated-surveillance-and-climate-informed-health-early-warning-systems.

- Drewry J; Oura CAL. ‘Strengthening climate resilient health systems in the Caribbean.’ Journal of Climate Change and Health. 2022; 6:100135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2022.100135.

- Pan American Health Organization. ‘EU and PAHO supporting nine Caribbean countries in integration of health into national adaptation plans.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.paho.org/en/news/19-8-2022-eu-and-paho-supporting-nine-caribbean-countries-integration-health-national.

- Pan American Health Organization. ‘UK FCDO – Smart hospitals in the Caribbean.’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://www.paho.org/en/partnerships/uk-fcdo-smart-hospitals-caribbean.

- DHIS 2 Team. ‘What is DHIS?’ 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. https://docs.dhis2.org/en/use/what-is-dhis2.html.