A closer look at South Africa’s approach

Both the 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the G20 have committed to triple renewables, but where is the money going to come from?

Climate change is particularly important for South Africa not just because of the way it’s affecting societies on the continent, including us, but also because we have a Just Energy Transition Partnership. That comes with many resources that have to be mobilised but are not delivering on the scale that is necessary. It will be interesting to see what comes out of the Task Force for the Global Mobilization Against Climate Change, created under Brazil’s G20 presidency this year.

South Africa has argued at COP meetings and in discussions about the JETP and elsewhere that we tend to get obsessed by the amount of money needed for climate finance. That is important of course, but we should also look at the quality of that money. We need to think about the balance between grants, highly concessional loans, market-related loans and so on. Whether deliberately or not, the JETP has been structured based on traditional development aid frameworks, but what is needed now is something that is flexible and adaptable and allows for creativity and innovation in how to deliver the finance. Also, development finance agencies have a particular way of doing things. But we are living in a world where all these things need to change. Without that change, ideas and projects cannot move forward as quickly as is necessary. The cost of the transition to South Africa has been calculated at over $100 billion. We’re getting only around $12 billion over a five-year period now through the JETP. That’s not going to cut it.

South Africa is a large player in the African Development Bank and the New Development Bank. Are they doing enough to provide climate finance?

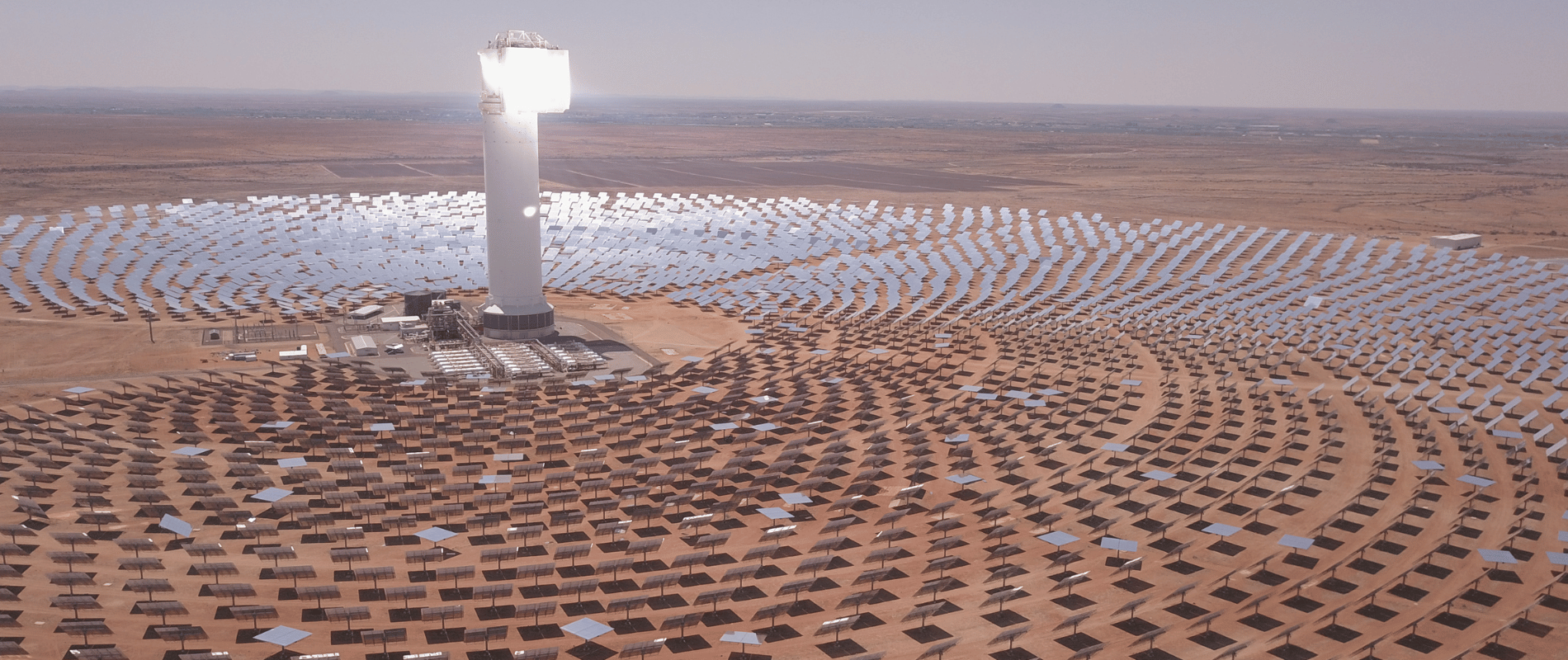

The NDB has provided support to South Africa in the areas of clean energy and energy efficiency over the last few years, including in a battery energy storage project and a renewable energy sector development project. There is also money from the AfDB, and also from the World Bank to decommission one of the coal-fired power stations. But such funding still needs to be scaled up further.

Plus we must not forget the social and developmental aspects. There can’t be a trade-off. It can’t be that you have to reduce your carbon footprint but you can’t roll out more coal-generated electricity to the townships, if the townships don’t have energy access. And how are we going to reskill all those workers, or, in the absence of being able to reskill them, how do we provide social safety protection for people who will be unable to be employed anywhere else? Our official unemployment rate is already around 33%. If that includes people who have given up looking for work it’s over 40%, plus we have a huge cohort of more than 55% of the population under the age of 25. So if people lose their jobs in the coal sector, that’s 90,000 workers who probably sustain at least half a million people, if not more.

It’s not just about financing the decommissioning of coal plants or building more solar plants. It’s also about skilling, reskilling and identifying what you’re going to do with people who aren’t in a position to retrain. We need to think about it broadly, in terms of communities rather than just the workers in the coal

mines or power stations.